Speech recognition and text-to-speech on the web

Implementing your own "Hey, Siri!" is not that hard.

Visit my ChatGPT With Voice project and you will see that it is not different from your everyday voice assistants, except much smarter, potentially dumber at times, and admittedly so much slower. Let's see how I equipped ChatGPT with the browser's modern speech APIs. If you care to find out in-depth, take a look at MDN's Web Speech API.

Speech recognition

Okay, I cheated a little here. You can implement speech recognition from scratch using SpeechRecognition, but react-speech-recognition was such a good library that it enabled me to move fast in the prototyping phase of my project, when I had to deal with setting up a backend that communicated with ChatGPT's APIs. Let's keep using it, shall we?

npm install react-speech-recognition

npm install -D @types/react-speech-recognition # If you use TypeScript

You might run into this error...

regeneratorRuntime is not defined

...in which case you should follow react-speech-recognition's troubleshooting guide by installing regenerator-runtime and import 'regenerator-runtime/runtime' at the top of your app's entry file.

react-speech-recognition provides us with a useSpeechRecognition() hook and a default SpeechRecognition export. SpeechRecognition controls the starting/stopping/aborting of speech recognition, while useSpeechRecognition() returns the state of the process as well as many other useful information.

Let's try implementing some common use cases.

Pressing a button to talk to the microphone

This standard feature is very simple to implement.

import SpeechRecognition, { useSpeechRecognition } from 'react-speech-recognition';

const Microphone = () => {

const {

transcript,

listening,

browserSupportsSpeechRecognition

} = useSpeechRecognition();

const handleClick = () => {

SpeechRecognition.startListening();

};

if (!browserSupportsSpeechRecognition) {

return <span>Browser doesn't support speech recognition.</span>;

}

return (

<div>

<p>Microphone: {listening ? 'on' : 'off'}</p>

<button onClick={handleClick}>Start</button>

<p>{transcript}</p>

</div>

);

};

By default, when you stop speaking, the microphone will automatically stop listening. However, this is only true on desktop. On mobile Safari, you need to manually stop by calling SpeechRecognition.startListening(), so let's make sure our code works on both desktop and mobile.

const handleClick = () => {

if (listening) {

SpeechRecognition.stopListening();

} else {

SpeechRecognition.startListening();

}

};

Another caveat on mobile is that browsers other than Safari, such as Chrome, don't seem to register any voice at all. I don't know why that is, because underneath they all use the same WebKit engine. This seems like a permission issue, though, since you don't see Chrome asking for permission to access the microphone as Safari does.

Sending a request after each voice command

We can get the final transcript from the useSpeechRecognition() hook to do something useful with it.

import { useEffect } from 'react';

import SpeechRecognition, { useSpeechRecognition } from 'react-speech-recognition';

const Microphone = () => {

const {

...,

finalTranscript,

} = useSpeechRecognition();

useEffect(() => {

if (finalTranscript) {

fetch('https://www.example.com', {

method: 'POST',

headers: { 'Content-Type': 'application/json' },

body: JSON.stringify({ text: finalTranscript }),

})

.then((res) => res.json())

.then(/* Do something useful */)

.catch(/* Handle error */);

}

}, [finalTranscript]);

return (

<div>

...

</div>

);

};

Text-to-speech

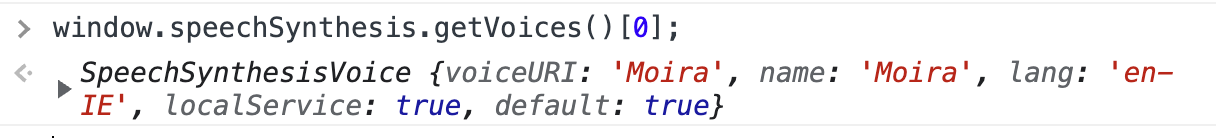

I can proudly say that I don't use a 3rd party library here, because the browser's APIs are simple enough. On most modern browsers, you can access the window.speechSynthesis object, which is the gateway to the text-to-speech engine of the underlying OS. Calling getVoices() on it and you get all the supported voices that the OS provides. Each voice object looks something like this.

Based on the information on each object, you can do more complicated things, such as grouping them by language like I did. For now, let's consider more straightforward examples.

Speaking a text out loud

voice and rate (or speed) are configurable parameters, among many others.

const utterance = new SpeechSynthesisUtterance(text);

utterance.voice = window.speechSynthesis.getVoices()[0]; // Else the default voice is used

utterance.rate = 1; // The default rate is 1

window.speechSynthesis.speak(utterance);

Allowing users to select their preferred voice

As previously mentioned, calling window.speechSynthesis.getVoices() would do the trick. One caveat you need to know is that system voices take some time to load, so the first time you call getVoices(), you might get an empty array back. To deal with this, listen to the voiceschanged event.

window.speechSynthesis.addEventListener('voiceschanged', () => {

// Voices are available now

});

Of course, Safari must give us headaches again. Even though CanIUse confirmed that this event is supported on Safari, in my case it is not fired at all. Therefore, for Safari and mobile browsers, I guess we are back to periodical checks. By the way, I'm using react-device-detect to sniff user agents.

import { isSafari, isMobile, isIOS } from 'react-device-detect';

if (isSafari || (isMobile && isIOS)) {

let interval = setInterval(() => {

const newVoices = window.speechSynthesis.getVoices();

if (newVoices.length > 0) {

clearInterval(interval);

// Voices are available now

}

}, 100);

// Stop checking after 10 seconds

setTimeout(() => clearInterval(interval), 10_000);

}

Conclusion

These are what I learned regarding speech recognition and text-to-speech from building a voice client for ChatGPT. They are what I set out to understand when I first started the project and I'm pleased that I have achieved my goals, but I also learned so much more about Azure, Ubuntu, and web servers. Stay tuned for my future blog posts.

In the meantime, thank you for reading till the end. As always, happy hacking everyone. 🤓